Information Sharing and the Named Person: finding a way through the current debate

The Named Person scheme is back in the news. More than a year on from the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Scottish Government has published new proposals designed to get Girfec (Getting it right for every child) implementation back on track with the Children and Young People (Information Sharing) (Scotland) Bill*.

But it hasn’t all been plain sailing. The Scottish Parliament’s scrutiny of the Bill led to some awkward questions for the Scottish Government.

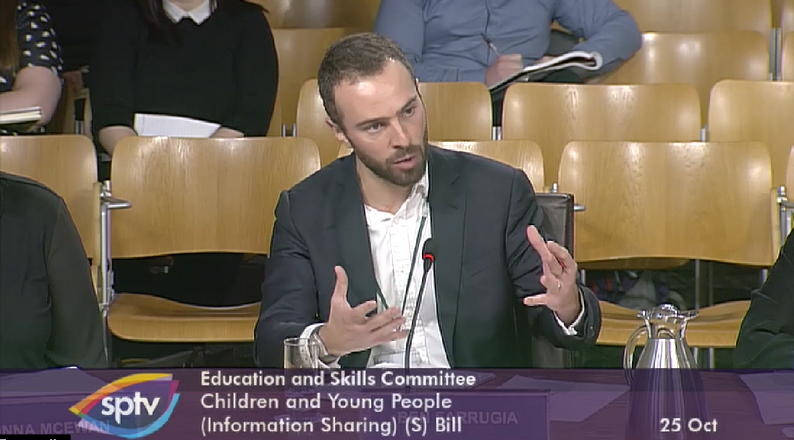

Once again people are questioning the viability of the Named Person scheme, and children’s organisations have had to publicly restate that Girfec is not just desirable, but essential. I was up in front of the Education and Skills Committee, on 25 October, to do just that. So what exactly is going on?

Bills, directives and codes of practice

Back in July 2016 the UK Supreme Court put the brakes on Scotland’s roll out of the Named Person and Child’s Plan. Although judges dismissed complaints that the Named Person service itself was unlawful, they did conclude that certain duties around information sharing had the potential to breach children and families’ rights to privacy.

The Scottish Government agreed to amend relevant sections of the law underpinning the Named Person and Child’s Plan, and following an extensive process of engagement with children, parents and professionals, they’ve come up with the Children and Young People (Information Sharing) (Scotland) Bill.

This Bill does a couple of important things. First, it removes the (not commenced yet) duty on Named Persons and supporting organisations to share information about children where doing so could help promote, secure or safeguard the child’s wellbeing. The Supreme Court felt this blanket ‘duty to share’ could lead to inappropriate information sharing between professionals, as the combination of a legal duty and different views about what constitutes a wellbeing concern could lead to blurred lines.

Secondly, instead of the ‘duty to share’, the Bill proposes a ‘duty to consider sharing’, requiring Named Persons and supporting organisations (e.g. police, colleges etc.) to consider sharing information about a child or family where this could safeguard or promote the child’s wellbeing. In weighing up whether to share personal information, the Named Person and others must always make decisions, and then act, within the existing legal framework of human rights and data protection law (i.e. Data Protection Act 1998).

And thirdly, to make sure information sharing is done properly, and to help professionals navigate what is a fairly complicated area of law, the Bill also introduces a statutory Code of Practice, which the Named Person and those sharing info with Named Persons would have to follow.

Views on the Info Sharing Bill

CELCIS has been contributing directly to the Scottish Parliament’s scrutiny of the Bill alongside many other children’s organisations. Our written submission to the Committee was typical of some feedback, arguing that Girfec is essential if we’re going to move from a system based on fire-fighting and sticking plasters, to one which can works with families at an early stage, before small issues become big problems. I had the opportunity, along with colleagues from the Centre of Youth and Criminal Justice, prisons, the police, the Care Inspectorate, and the Children’s Commissioner, to make this case in person, at an Education and Skills Committee Evidence Session.

But while there is widespread support for the Bill’s objectives, there is also criticism on its detail. In particular, with the illustrative Code of Practice, which people felt was opaque and not sufficiently practice-focused. The Scottish Government is right when it says that some professionals choose not to share information which could have kept a child safe. And parents themselves frequently express frustration at the defensive posture of professionals, who appear unwilling to make connections with other service providers in case they fall foul of the much-feared (and little understood) ‘data protection law’.

The answer to these problems wasn’t, however, the original ‘duty to share’ (as our briefing in 2013 stated clearly) and it isn’t, on its own, the new Information Sharing Bill.

That’s because information sharing is complicated. It was complicated before Girfec was around, and it will still be complicated when Gifec is standard practice across Scotland. And it should be, for to do information sharing well, within the parameters of the law, professionals need to feel confident and supported. They need to have access to relevant, accessible guidance, and have informed people who they can turn to for help. They need opportunities to learn and discuss the issues with colleagues in other professions, and they need good, robust systems within and between organisations for the safe storage and transfer of information. And, they absolutely need the space and time to build relationships with children and families, establishing trust, and having the opportunity to explain why and when the sharing of information might be necessary.

Recent developments

On 8 November the Deputy First Minister, John Swinney, faced the Education and Skills Committee. He was quick to emphasise that the Scottish Government had listened carefully to the evidence provided to the Committee, and acknowledged some of the concerns which had been raised. In response, he gave a commitment to re-develop the Code of Practice in close partnership with child welfare experts, and to amend the Bill. He also announced the establishment of a Girfec Practice Development Panel (to oversee broader practice guidance and other activities) and promised to increase the financial resources available for implementation. All significant and welcome developments.

It’s important to remember that information sharing won’t ever stop being complicated for professionals. But if implementation of the new Bill is done right, Scotland could start to turn the promise of Girfec into a reality.

*A ‘Bill’ is essentially a draft law, and Governments or opposition MSPs have to introduce these to Parliament for them to scrutinise, debate and amend before they are finally rejected, or approved (which then turns them into law, an ‘Act’). At various stages of this process the relevant parliamentary committee (a small group of MSPs) takes evidence from organisations and individuals with insight or expertise on the issues which the Bill addresses. The Children and Young People (Information Sharing) Bill was laid before Parliament by Deputy First Minister John Swinney on 22 June 2017.

The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author/s and may not represent the views or opinions of CELCIS or our funders.

Commenting on the blog posts

Sharing comments and perspectives prompted by the posts on this blog are welcome. CELCIS operates a moderation process so your comment will not go live straight away.